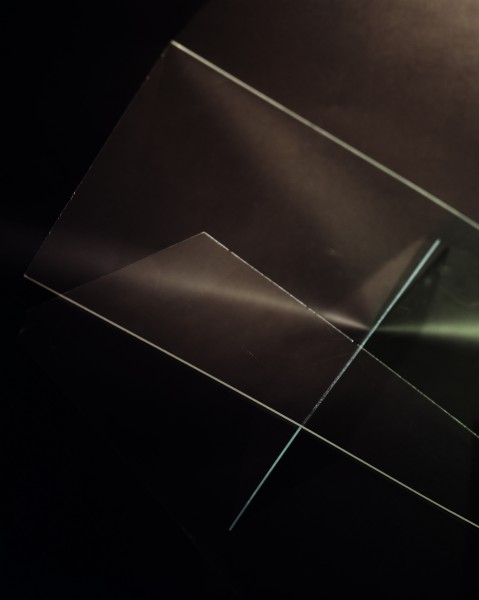

Studio Construct 118, 2011

Sep 27, 2011

By Regan Golden-McNerney

Since the 1970s, Barbara Kasten has been developing a distinct approach to abstract photography. Inspired by the simple forms used by Bauhaus artists from the 1930s, Kasten begins her process by arranging basic shapes and colored backdrops atop glass and mirrors. These “constructions” are photographed at dramatic angles, using traditional cameras and printed digitally. Kasten describes her work as “concrete photography” because her goal, as she explained in a recent interview with photographer Heidi Norton, is not to render the physical world immaterial, but to make something as ephemeral as light palpable as it bounces off reflective objects and surfaces. In her current exhibition at Tony Wight Gallery, Kasten’s photographs, created between 1974 and 2011, are linked together by her consistent approach and interest in light.

In her photographs from the early 1980s, brilliant light illuminates vibrant yellow triangles and green cubes, setting up a sharp contrast between these objects and a white backdrop. In a gradual shift over the past three decades, Kasten’s new photographs relish the ambiguity that light and shadow can create on translucent objects set against a neutral backdrop, obscuring the borders in bright light or erasing them with shadow. In “Studio Construct 118,” 2011, two thin sheets of pale green glass cut across a warm black background, edges illuminated. The objects in Kasten’s new “constructions” are only vaguely identifiable, and turn out to be materials that are typically peripheral to a studio photographer’s practice: leftover sheets of glass or disposable rolls of Seamless Paper used as quick backdrops. These materials are placed slightly askew in precarious, suspended arrangements, creating visual puzzles of glass and paper.

Despite these ephemeral materials, there is a remarkable tactility to Kasten’s new large digital photographs in which any shift in color or crease in the surface appears monumental. In the photograph “Studio Construct 125,” 2011, panes of glass gently lean against each other, but the corner of the glass has made a small hole in the gray backdrop paper suspended behind it. There is incredible tension between these two materials: the sheets of glass seem poised to cut through the paper background, while the slight slope of the paper suggests it will soon send the glass sliding onto the floor. Kasten’s photographs are less an attempt to transcend everyday surfaces toward a pure form of abstraction, and more an attempt to expose their plain and simple beauty.

Kasten’s “Studio Constructs” could be read as individual observations of small changes in the studio that fail to connect to the outside world, but the works actually have the opposite effect of making us more aware of the subtle shifts in light and atmosphere around us. Abstract photography is sometimes dismissed as detached from reality, but this is far from what its progenitors anticipated. Abstraction was invested with idealism by artists like Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, one of Kasten’s influences, and Josef Albers, who both taught at the Bauhaus in Weimar Germany before fleeing to the United States prior to World War II. They argued that abstract art could improve society as a model of efficiency and accessibility. Albers wrote, “Our desire for the simplest and clearest forms will make mankind more united.” There was a sense that abstraction was the visual vocabulary of their time and the best way to invoke an orderly new reality. Today, abstraction is one of a myriad of ways that artists work, so what explains its resurgence, or its particular relevance at present? Is it escapism into the realm of color and form, an avoidance of the political, or a way of refocusing on the “concrete” in a world awash in virtual reality

The subtle materiality in Kasten’s work suggests the latter is true, but this might also be said about several exhibitions of abstract art in Chicago over the past year: from the gritty paintings by Philip Vanderhyden at Andrew Rafacz this past spring, to the photographs of ink drawings on wrinkled aluminum by Anthony Pearson at Shane Campbell last fall. Both artists, like Kasten, use a limited palette of neutral colors to reveal subtle changes in a textured surface. This is quite different from the work of contemporary abstract artists like Odili Donald Odita’s shiny, colorful paintings on Plexiglas, or Walead Beshty’s vividly colored photograms. Both artists’ works resonate more with Kasten’s work from the 1980s in their combination of angular forms and intense color, so perhaps what we have been seeing in Chicago over the past year is an approach to abstraction that puts texture before color, ambiguity before clarity, and reminds us of the scuffed-up surfaces of everyday objects, rather than the cleanliness of form that Albers and Moholy-Nagy first envisioned as being integral to abstract art.

Barbara Kasten shows at Tony Wight Gallery, 845 West Washington, through October 22.